Tom (WordWulf) Sterner is a writer, vocalist & multi/media artist.

A native of Colorado, he lives in Arvada with his wife, Kathy.

Email: [email protected]

A native of Colorado, he lives in Arvada with his wife, Kathy.

Email: [email protected]

Interview by WhoHub

What did you first read? How did you begin to write? Who were the first to read what you wrote?

I read about Dick, Jane, Sally, and Spot in elementary school. I remember reading "The Boxcar Children" and dreaming about taking my seven younger siblings and living in an abandoned boxcar far away from my alcoholic father and Catholic mother. Obsessed with animals as a Child, I read everything I could get my hands on about horses and dogs. English teachers were the first to read what I wrote. I caught a lot of flak for 'inventing words.'

What is your favorite genre? Can you provide a link to a site where we can read some of your work or learn something about it?

I don't have a favorite genre, would like to think that if a writer lives long enough and writes long enough, he/she becomes a genre. My work may be sampled at http://wordwulf.com You can also Google 'WordWulf' or 'Tom Sterner'.

What is your creative process like? What happens before sitting down to write?

My creative process kicked in when I was around eight years old. I've never been able to take it out of gear. It has run off the tracks and is rumbling north toward eventual oblivion. I don't sit down to write. I stand up and scream and the voices won't stop so I howl, laugh into their tongue faces and write 'em down. There are no corners in a room that's round.

What type of reading inspires you to write?

Reading doesn't inspire me to write, although current events sometimes incite me to riot. I enjoy writing into the very teeth of them.

What do you think are the basic ingredients of a story?

The beginning and end, obviously, engagement and pathos, where one can be the other, beginning and end. Middle scene and nowhere to go, the reader must not know what I know.

What voice do you find most to your liking: first person or third person?

I like 'em both. He sees the girl running; she touches my hand. "I am a good girl, face of doom." There's a mess on the rug, lilacs and blood. "Woman of dreams, I am." Asleep on the parkbench, newspaper man; his taste for afternoon darkness, spent and splashed in basement bathrooms beneath the pavilion. I'm a singer in the band.

What well known writers do you admire most?

Abraham Lincoln, Jesus Christ, Friedrich Nietzsche, Herman Hesse, James Douglas Morrison, Stephen King, Larry McMurtry, Toni Morrison, John Steinbeck, James Clavell, Edgar Allan Poe.

What is required for a character to be believable? How do you create yours?

Those people bumping around inside my head have to feel, become disgusting and heroic through their flaws and terrorize my psyche until, unable to sleep or be completely awake, I give up ground and write them down. It is little enough to make anyman scream.

Are you equally good at telling stories orally?

Yes and those stories told orally generally rip through the room and carom off the rails in fits tragic/comedic, pale visitors and completely ignorant of the intent of origin.

Deep down inside, who do you write for?

Myself. As a much younger man, I had vision and purpose, a message to convey to the masses. I slept with tablets and pens under my pillow. Given the choice of whether to wipe my ass with the last bit of toilet paper or use it to write a thought lest I lose it, ink was the answer. Vision and purpose set aside, I write because it is that which I must do. Like breathing, it means to me that I am living. If I don't, I'm not.

Is writing a form of personal therapy? Are internal conflicts a creative force?

Of course internal conflicts are a creative force; so are internal epiphanies. Writing is an event of catharsis, a decided leaning toward chaos.

Does reader feed-back help you?

Reader feed-back is useful in the process of creativity. When a piece is done, it is done. Reader feed-back then is an interpretation of ends, an invitation, perhaps, to future levels of engagement.

Do you participate in competitions? Have you received any awards?

I do and I have. Several of my short stories and poems have won contests. I have won the Maria Cerjak award for avant/garde writing. In 2006 and 2008 I was nominated for the Pushcart Prize.

Do you share rough drafts of your writings with someone whose opinion you trust?

I usually do, especially when writing novels. It helps to have someone look in the window.

Do you believe you have already found "your voice" or is that something one is always searching for?

I've 'accepted' mine, discovered the seek invites internal madness and is disruptive to the creative process in general.

What discipline do you impose on yourself regarding schedules, goals, etc.?

Creatively, I am out of control and finally comfortable with that.

What do you surround yourself with in your work area in order to help your concentrate?

I have photographs of my Children when they were Children, Frazetta's 'Death Dealer', on the wall before me. The living voices of my son, Zedidiah, and his friends in the other room, their exclamations of victory while playing 'Guitar Hero' are a positive audio drop just the other side of the wall. The woman I love trip-hammers my heart and tickles my blood ecstatic as she cavorts behind my eyes and teases me with messages erotic/domestic. These are paths through the forest I walk until I dissolve into the unreal reality of the creative process where I exist until the path slaps me in the face and shocks me back to that other place.

Do you write on a computer? Do you print frequently? Do you correct on paper? What is your process?

My pen speaks. I keep a hundred of them around and tablets in stacks. My first edit is usually the process of transferring ink to glass. I hard copy everything, unable to trust the machine because, sometimes, the glass is dead.

What sites do you frequent on-line to share experiences or information?

Narcissistic in that regard, I am interested in those of a like mind, particularly those who publish my work. Currently, Michael Palecek's "New American Dream" has my attention. My brother owl, Michael Annis, fascinates and engages me with his work and the publishing of myself and other monsters at "Howling Dog Press." His byline, "Home of the most dangerous writers alive" resonates well with me. We have a shared vision, "Poetry Nuclear," smoldering a hundred miles inside and destined to erupt.

What has been your experience with publishers?

The word "submission" is revolting to me, the invitation to rejection or acceptance based on what? The room is full of girls. I am mad to danse through their faces.

What are you working on now?

I'm developing sequels to two of my novels and seeking a screenwriter to develop one of them and a short story for "Submission" to markets. My son, Tommy, lead guitarist in the metal group, "Illicit Sects" (http://illicitsects.com ), is working with me to record a thousand songs I wrote and didn't manage to get tracked on a couple of CD's I did.

What do you recommend I do with all those things I wrote years ago but have never been able to bring myself to show anyone?

Keep writing and bury your past work, archive it. Keep 13 pieces out in the "submission" process at all times. Bring your past work up to date and submit a bit of it once in a while. Develop a thick skin and endeavor to surround each piece with a forest of rejection slips until one of them becomes the tree someone discovered in that forest lost.

http://www.whohub.com/wordwulf#

What did you first read? How did you begin to write? Who were the first to read what you wrote?

I read about Dick, Jane, Sally, and Spot in elementary school. I remember reading "The Boxcar Children" and dreaming about taking my seven younger siblings and living in an abandoned boxcar far away from my alcoholic father and Catholic mother. Obsessed with animals as a Child, I read everything I could get my hands on about horses and dogs. English teachers were the first to read what I wrote. I caught a lot of flak for 'inventing words.'

What is your favorite genre? Can you provide a link to a site where we can read some of your work or learn something about it?

I don't have a favorite genre, would like to think that if a writer lives long enough and writes long enough, he/she becomes a genre. My work may be sampled at http://wordwulf.com You can also Google 'WordWulf' or 'Tom Sterner'.

What is your creative process like? What happens before sitting down to write?

My creative process kicked in when I was around eight years old. I've never been able to take it out of gear. It has run off the tracks and is rumbling north toward eventual oblivion. I don't sit down to write. I stand up and scream and the voices won't stop so I howl, laugh into their tongue faces and write 'em down. There are no corners in a room that's round.

What type of reading inspires you to write?

Reading doesn't inspire me to write, although current events sometimes incite me to riot. I enjoy writing into the very teeth of them.

What do you think are the basic ingredients of a story?

The beginning and end, obviously, engagement and pathos, where one can be the other, beginning and end. Middle scene and nowhere to go, the reader must not know what I know.

What voice do you find most to your liking: first person or third person?

I like 'em both. He sees the girl running; she touches my hand. "I am a good girl, face of doom." There's a mess on the rug, lilacs and blood. "Woman of dreams, I am." Asleep on the parkbench, newspaper man; his taste for afternoon darkness, spent and splashed in basement bathrooms beneath the pavilion. I'm a singer in the band.

What well known writers do you admire most?

Abraham Lincoln, Jesus Christ, Friedrich Nietzsche, Herman Hesse, James Douglas Morrison, Stephen King, Larry McMurtry, Toni Morrison, John Steinbeck, James Clavell, Edgar Allan Poe.

What is required for a character to be believable? How do you create yours?

Those people bumping around inside my head have to feel, become disgusting and heroic through their flaws and terrorize my psyche until, unable to sleep or be completely awake, I give up ground and write them down. It is little enough to make anyman scream.

Are you equally good at telling stories orally?

Yes and those stories told orally generally rip through the room and carom off the rails in fits tragic/comedic, pale visitors and completely ignorant of the intent of origin.

Deep down inside, who do you write for?

Myself. As a much younger man, I had vision and purpose, a message to convey to the masses. I slept with tablets and pens under my pillow. Given the choice of whether to wipe my ass with the last bit of toilet paper or use it to write a thought lest I lose it, ink was the answer. Vision and purpose set aside, I write because it is that which I must do. Like breathing, it means to me that I am living. If I don't, I'm not.

Is writing a form of personal therapy? Are internal conflicts a creative force?

Of course internal conflicts are a creative force; so are internal epiphanies. Writing is an event of catharsis, a decided leaning toward chaos.

Does reader feed-back help you?

Reader feed-back is useful in the process of creativity. When a piece is done, it is done. Reader feed-back then is an interpretation of ends, an invitation, perhaps, to future levels of engagement.

Do you participate in competitions? Have you received any awards?

I do and I have. Several of my short stories and poems have won contests. I have won the Maria Cerjak award for avant/garde writing. In 2006 and 2008 I was nominated for the Pushcart Prize.

Do you share rough drafts of your writings with someone whose opinion you trust?

I usually do, especially when writing novels. It helps to have someone look in the window.

Do you believe you have already found "your voice" or is that something one is always searching for?

I've 'accepted' mine, discovered the seek invites internal madness and is disruptive to the creative process in general.

What discipline do you impose on yourself regarding schedules, goals, etc.?

Creatively, I am out of control and finally comfortable with that.

What do you surround yourself with in your work area in order to help your concentrate?

I have photographs of my Children when they were Children, Frazetta's 'Death Dealer', on the wall before me. The living voices of my son, Zedidiah, and his friends in the other room, their exclamations of victory while playing 'Guitar Hero' are a positive audio drop just the other side of the wall. The woman I love trip-hammers my heart and tickles my blood ecstatic as she cavorts behind my eyes and teases me with messages erotic/domestic. These are paths through the forest I walk until I dissolve into the unreal reality of the creative process where I exist until the path slaps me in the face and shocks me back to that other place.

Do you write on a computer? Do you print frequently? Do you correct on paper? What is your process?

My pen speaks. I keep a hundred of them around and tablets in stacks. My first edit is usually the process of transferring ink to glass. I hard copy everything, unable to trust the machine because, sometimes, the glass is dead.

What sites do you frequent on-line to share experiences or information?

Narcissistic in that regard, I am interested in those of a like mind, particularly those who publish my work. Currently, Michael Palecek's "New American Dream" has my attention. My brother owl, Michael Annis, fascinates and engages me with his work and the publishing of myself and other monsters at "Howling Dog Press." His byline, "Home of the most dangerous writers alive" resonates well with me. We have a shared vision, "Poetry Nuclear," smoldering a hundred miles inside and destined to erupt.

What has been your experience with publishers?

The word "submission" is revolting to me, the invitation to rejection or acceptance based on what? The room is full of girls. I am mad to danse through their faces.

What are you working on now?

I'm developing sequels to two of my novels and seeking a screenwriter to develop one of them and a short story for "Submission" to markets. My son, Tommy, lead guitarist in the metal group, "Illicit Sects" (http://illicitsects.com ), is working with me to record a thousand songs I wrote and didn't manage to get tracked on a couple of CD's I did.

What do you recommend I do with all those things I wrote years ago but have never been able to bring myself to show anyone?

Keep writing and bury your past work, archive it. Keep 13 pieces out in the "submission" process at all times. Bring your past work up to date and submit a bit of it once in a while. Develop a thick skin and endeavor to surround each piece with a forest of rejection slips until one of them becomes the tree someone discovered in that forest lost.

http://www.whohub.com/wordwulf#

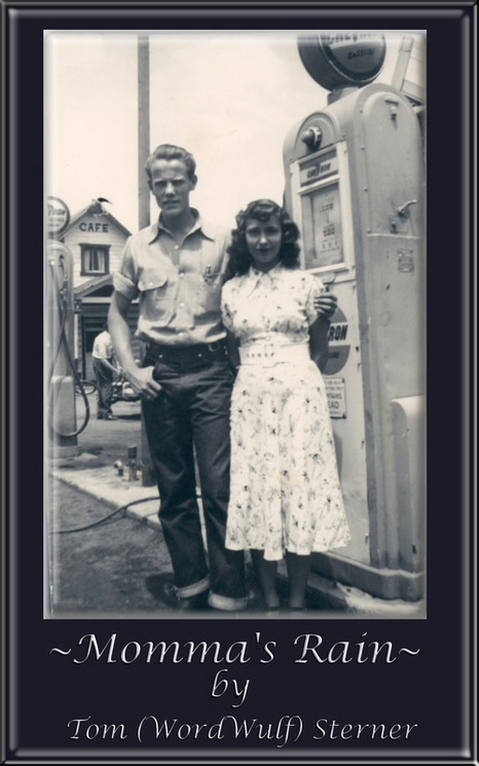

Momma's Rain - Now available through Amazon.com for $12.63 in paperback and downloadable to Kindle (e-book) for $4.99.

The shocking true story of alcoholism, child and spousal abuse from the inside looking out. Order Momma’s Rain by emailing author [email protected] or use BUY button above..

Momma's Rain Reviews

October 21, 2010

“Cars drove slow; neighbors looked out windows at six children sitting on a couch in the gutter, behind them, a small mountain of garbage, their world belongings.”

This is the life the author did not live but his seven siblings fought each day to survive. As many adopted children do, Sterner at nineteen, felt the urge to understand his family – to understand his abandonment. This remarkable explanation is told through his brother’s eyes.

Momma’s Rain is a fascinating account of a life full of dead eyes, poverty, abuse, addiction, and yet; survival, hope and love. Every day Momma tries to avoid an invisible trap wire that could send her flying into too many pieces and if that happened what would happen to the children. The trap, an abusive drunk, her husband. No one knew when he would go off and the beatings (mental and physical) would begin.

As the story progresses, Momma and her son Timmy must consider the mysteries of their life in a world filled with impulses of curiosity along with the complexity of surviving nature, life and death. The experiences range from Momma battling for ways to feed her children to Timmy meeting a unique human angel. This peaceful wise lady gives him, among things, the gift of knowing that all life is not like his.

Momma’s Rain is hard to put down. It is profound in feeling. Sterner takes you deep inside the abyss of alcoholism and poverty to the trusting tender relationship between mother and son with each occurrence launching a valued life lesson.

Sterner meticulously collected the straws of his lost family life and spun them into an explicit account of a family whose focus stayed faithful to their bond, “We stand our ground, fight our fights, lick our wounds and keep our mouths shut.” Now that Momma is gone, her story is being shared. Momma lived side by side with her grief. Like the tears that ran down her face, grief was a thunderous driving rainstorm. It can open up to the emergence of the sun and with a rainbow of promise for the future. Hopefully, by telling this story, the family and the people who read this book will see the rainbow.

An emotionally stirring book embracing the boundless promise that no matter what – there is hope. Momma’s Rain - highly recommended.

Sherry Russell MS BCETS BCBT

Conquering the Mysteries and Lies of Grief

www.catchafallinglife.com

[email protected]

“Cars drove slow; neighbors looked out windows at six children sitting on a couch in the gutter, behind them, a small mountain of garbage, their world belongings.”

This is the life the author did not live but his seven siblings fought each day to survive. As many adopted children do, Sterner at nineteen, felt the urge to understand his family – to understand his abandonment. This remarkable explanation is told through his brother’s eyes.

Momma’s Rain is a fascinating account of a life full of dead eyes, poverty, abuse, addiction, and yet; survival, hope and love. Every day Momma tries to avoid an invisible trap wire that could send her flying into too many pieces and if that happened what would happen to the children. The trap, an abusive drunk, her husband. No one knew when he would go off and the beatings (mental and physical) would begin.

As the story progresses, Momma and her son Timmy must consider the mysteries of their life in a world filled with impulses of curiosity along with the complexity of surviving nature, life and death. The experiences range from Momma battling for ways to feed her children to Timmy meeting a unique human angel. This peaceful wise lady gives him, among things, the gift of knowing that all life is not like his.

Momma’s Rain is hard to put down. It is profound in feeling. Sterner takes you deep inside the abyss of alcoholism and poverty to the trusting tender relationship between mother and son with each occurrence launching a valued life lesson.

Sterner meticulously collected the straws of his lost family life and spun them into an explicit account of a family whose focus stayed faithful to their bond, “We stand our ground, fight our fights, lick our wounds and keep our mouths shut.” Now that Momma is gone, her story is being shared. Momma lived side by side with her grief. Like the tears that ran down her face, grief was a thunderous driving rainstorm. It can open up to the emergence of the sun and with a rainbow of promise for the future. Hopefully, by telling this story, the family and the people who read this book will see the rainbow.

An emotionally stirring book embracing the boundless promise that no matter what – there is hope. Momma’s Rain - highly recommended.

Sherry Russell MS BCETS BCBT

Conquering the Mysteries and Lies of Grief

www.catchafallinglife.com

[email protected]

by Martha A. Cheves, Author of Stir, Laugh, Repeat

“I was four-years-old in 1935. My mother took my twin brother and me to a mountain park in Colorado Springs for our birthday. It was July 31st, a hot and sultry summer day in Colorado. We rode ponies round and round the pony pole, my brother and me. I’ll never forget the flies, deer flies I think. They were huge and aggressive. They bit. After lunch Mother told me to go into the outhouse to go potty. I didn’t really have to go but would not consider speaking back to Mother ever, not in any way. She closed the door and I waited. When I tried to leave the shack with the dark stinky hole and light shooting through cracks in the wall, I discovered I was locked in. I began to cry. I never saw Mother again. I’ll never forget the flies, deer flies I think. They were huge and aggressive. They bit.” ‘This is the first story my uncle told me when I found him. That was in 1982 when I was nineteen-years-old. I was abandoned at Denver General Hospital in 1963 when I was born. My Mother put me up for adoption. She felt her eighth child should have a better chance in life then the seven before. Odd, but fitting, that I would find my uncle first when I came of age and went searching for my real family. He and I are the cull, those cut from the herd and left to forge on their own.’

It’s the winter of 1957 in Billings Montana. At seven years old, Timmy is the oldest child in the Turner family. At this time he has two younger brothers and a two year old sister. But more will come bringing the number of children in his family to seven, all before he reaches the age of twelve. Timmy’s dad is a roofer, a job that is dictated by the weather. He’s also an alcoholic and a mean one at that. Timmy’s brother Jerry as well as his mother can vouch for that. Almost daily Jerry will do something that his dad doesn’t like leading to a beating with the belt and standing in the corner. And heaven forbid if he comes home drunk, looking for a fight. That's when Timmy's mother gets the bad end of his fist and boot.

Timmy’s mother, Kathy, is the glue that keeps the family together. She does everything she can to keep a roof over their heads and food on the table. His dad, on the other hand, will blow every penny he can get his hands on to keep him in alcohol. The kids can go hungry and the landlord can evict them, as long as he has his drinking money. And that’s exactly what happened more often than not. They are constantly without food and being removed from their "living space" by the Sheriff at the request of the owner.

Reading Momma’s Rain filled me with many feelings, most from my own childhood. When I was in elementary school there were kids that I feel sure fit in with the life lead by Timmy and his family. And just as it happened when Timmy went to school, we kept our distance from these kids. We never gave thought to the possibility that these kids were possibly being beaten at home, that they might be hungry, and not just hungry for food but also for a kind word and a little friendship. We never gave much thought that they might be smart, even smarter than we were. After all they had to be to survive what they went through daily.

Author Tom Sterner has written a book that will break the hearts of every reader. It will also wake the reader up to the injustice most of us seem to perform not only as children but also as adults. It’s made me see the man or woman on the street with a different eye. One with even more compassion for them and their challenge to survive. I recommend that you not only read Momma’s Rain but that you also teach the lessons learned to the kids and grandkids in your life.

Now I wait impatiently to read the continuation – Momma’s Fire. It can only get better for these kids, I hope.

349 Pages

ISBN# 978-0954484699

Visit Martha’s SitesJ

http://marthaskitchenkorner.blogspot.com (A Book and A Dish)

http://stirlaughrepeat.blogspot.com

http://marthaatkitchenkorner.blogspot.com

http://marthasrecipecabinet.blogspot.com

http://stirlaughrepeatcookbook.blogspot.com

“I was four-years-old in 1935. My mother took my twin brother and me to a mountain park in Colorado Springs for our birthday. It was July 31st, a hot and sultry summer day in Colorado. We rode ponies round and round the pony pole, my brother and me. I’ll never forget the flies, deer flies I think. They were huge and aggressive. They bit. After lunch Mother told me to go into the outhouse to go potty. I didn’t really have to go but would not consider speaking back to Mother ever, not in any way. She closed the door and I waited. When I tried to leave the shack with the dark stinky hole and light shooting through cracks in the wall, I discovered I was locked in. I began to cry. I never saw Mother again. I’ll never forget the flies, deer flies I think. They were huge and aggressive. They bit.” ‘This is the first story my uncle told me when I found him. That was in 1982 when I was nineteen-years-old. I was abandoned at Denver General Hospital in 1963 when I was born. My Mother put me up for adoption. She felt her eighth child should have a better chance in life then the seven before. Odd, but fitting, that I would find my uncle first when I came of age and went searching for my real family. He and I are the cull, those cut from the herd and left to forge on their own.’

It’s the winter of 1957 in Billings Montana. At seven years old, Timmy is the oldest child in the Turner family. At this time he has two younger brothers and a two year old sister. But more will come bringing the number of children in his family to seven, all before he reaches the age of twelve. Timmy’s dad is a roofer, a job that is dictated by the weather. He’s also an alcoholic and a mean one at that. Timmy’s brother Jerry as well as his mother can vouch for that. Almost daily Jerry will do something that his dad doesn’t like leading to a beating with the belt and standing in the corner. And heaven forbid if he comes home drunk, looking for a fight. That's when Timmy's mother gets the bad end of his fist and boot.

Timmy’s mother, Kathy, is the glue that keeps the family together. She does everything she can to keep a roof over their heads and food on the table. His dad, on the other hand, will blow every penny he can get his hands on to keep him in alcohol. The kids can go hungry and the landlord can evict them, as long as he has his drinking money. And that’s exactly what happened more often than not. They are constantly without food and being removed from their "living space" by the Sheriff at the request of the owner.

Reading Momma’s Rain filled me with many feelings, most from my own childhood. When I was in elementary school there were kids that I feel sure fit in with the life lead by Timmy and his family. And just as it happened when Timmy went to school, we kept our distance from these kids. We never gave thought to the possibility that these kids were possibly being beaten at home, that they might be hungry, and not just hungry for food but also for a kind word and a little friendship. We never gave much thought that they might be smart, even smarter than we were. After all they had to be to survive what they went through daily.

Author Tom Sterner has written a book that will break the hearts of every reader. It will also wake the reader up to the injustice most of us seem to perform not only as children but also as adults. It’s made me see the man or woman on the street with a different eye. One with even more compassion for them and their challenge to survive. I recommend that you not only read Momma’s Rain but that you also teach the lessons learned to the kids and grandkids in your life.

Now I wait impatiently to read the continuation – Momma’s Fire. It can only get better for these kids, I hope.

349 Pages

ISBN# 978-0954484699

Visit Martha’s SitesJ

http://marthaskitchenkorner.blogspot.com (A Book and A Dish)

http://stirlaughrepeat.blogspot.com

http://marthaatkitchenkorner.blogspot.com

http://marthasrecipecabinet.blogspot.com

http://stirlaughrepeatcookbook.blogspot.com

Prologue

Six-year-old Jerry snuck into the bread last night. He ate the last two slices. He took quite a beating when Momma informed Daddy there was no bread for his lunch the next day. Jerry’s lips are stuck shut with dried blood, his forehead bruised from being slammed into the corner where he’s standing, smiling inside. His belly’s full. They can beat him all they want. The next morning he is gone and his four-year-old brother, Peter, with him. Where did they go, the police want to know. So does Momma and seven-year-old Timmy, Jerry’s brother and oldest of the Turner children.

The tenement is on fire. Flame tongues lick the walls on the fourth floor where the Turners live. The linoleum is a living thing, bubbling and breathing, belching cockroaches up from the lower floors. Daddy is passed out drunk and Momma frantic to wake him to save him, to save them, her seven children. He doesn’t disappoint her as he comes awake, swats her away, “Get off me, bitch!” A hero emerges from the drunken bag of his body, finds a way to save them all.

Momma was a Catholic, Daddy was a drunk. Momma was born in a chicken coop behind her grandfather’s mansion in the Ozarks, Missouri before he hung himself and blew his brains out over gambling debts and slave blood. Her father was the ashamed half-breed offspring of this white man and his Cherokee slave woman. At four-years-old, she was abandoned to a Catholic orphanage along with her two older sisters.

Daddy was born on a ranch in Colorado Springs, Colorado, a twin and his mother’s favorite. His twin brother was left in an outhouse at a campground in the mountains on his fourth birthday. His momma, unhappy in her marriage to a ranch hand, had found herself a new man who refused to take on the responsibility of two little bastards. She kept Daddy, threw the other one away. Her new man disciplined the boy with an iron hand and a coal shovel.

I lived the life and Momma told me the stories of life before me. She didn’t like it much that I wrote things down and made songs to sing out of the fabric of our lives and her tales. She needed me though and I think she was desperate to tell it all, to give her life substance. I swore an oath not to breathe a word of it to a soul until she was gone. She is passed, the grass grown long over the paths she walked. I am the son alive in the mist, no umbrella, of Momma’s Rain.

Six-year-old Jerry snuck into the bread last night. He ate the last two slices. He took quite a beating when Momma informed Daddy there was no bread for his lunch the next day. Jerry’s lips are stuck shut with dried blood, his forehead bruised from being slammed into the corner where he’s standing, smiling inside. His belly’s full. They can beat him all they want. The next morning he is gone and his four-year-old brother, Peter, with him. Where did they go, the police want to know. So does Momma and seven-year-old Timmy, Jerry’s brother and oldest of the Turner children.

The tenement is on fire. Flame tongues lick the walls on the fourth floor where the Turners live. The linoleum is a living thing, bubbling and breathing, belching cockroaches up from the lower floors. Daddy is passed out drunk and Momma frantic to wake him to save him, to save them, her seven children. He doesn’t disappoint her as he comes awake, swats her away, “Get off me, bitch!” A hero emerges from the drunken bag of his body, finds a way to save them all.

Momma was a Catholic, Daddy was a drunk. Momma was born in a chicken coop behind her grandfather’s mansion in the Ozarks, Missouri before he hung himself and blew his brains out over gambling debts and slave blood. Her father was the ashamed half-breed offspring of this white man and his Cherokee slave woman. At four-years-old, she was abandoned to a Catholic orphanage along with her two older sisters.

Daddy was born on a ranch in Colorado Springs, Colorado, a twin and his mother’s favorite. His twin brother was left in an outhouse at a campground in the mountains on his fourth birthday. His momma, unhappy in her marriage to a ranch hand, had found herself a new man who refused to take on the responsibility of two little bastards. She kept Daddy, threw the other one away. Her new man disciplined the boy with an iron hand and a coal shovel.

I lived the life and Momma told me the stories of life before me. She didn’t like it much that I wrote things down and made songs to sing out of the fabric of our lives and her tales. She needed me though and I think she was desperate to tell it all, to give her life substance. I swore an oath not to breathe a word of it to a soul until she was gone. She is passed, the grass grown long over the paths she walked. I am the son alive in the mist, no umbrella, of Momma’s Rain.

For life is a fiction

birth - a sad truth

death - a just reward

still Children smile

Chapter One

Children in Passing

I don’t like Country Western music

Billings Montana

Winter, 1957

Momma and Daddy rolled their boy child’s lifeless body into a blanket. Daddy reared back and kicked the package a couple of times. It didn’t offer much resistance. Six-year-old Jerry weighed less than forty pounds and was just over three feet tall. Daddy’s foot almost went through him.

“Stop kicking it!” Momma hissed. “We have to find a bridge to throw it off.”

“I’m whippin’ the l’il bastard’s ass one more time!” Daddy insisted, “L’il sumbitch thinks he can steal my lunch bread and get away with it. I’ll show ‘im!”

Jerry scrunched his eyes shut. His nose and cheeks were numb with cold, his face wedged in the corner, icy walls indifferent to his plight. Daddy had stuck him there hours ago, daring him to move, daring him to breathe. Daddy dared Jerry to even think. Jerry, lying little bastard that he was, promised after each punch and slap from Daddy’s hand that he would never steal the family’s bread again. He would not move, he would not breathe, he would not think.

Jerry wiggled his nose, cringed inside, hoped no one noticed; he moved. His ribs hurt where Daddy kicked him when he fell down when Daddy hit him. They hurt so he breathed in shallow little gasps of breath, cringed inside, hoped no one noticed; he breathed. Yes, he was a lying little bastard. He stood in the corners of this house, naked half the time and cold, imagined a plethora of scenarios of death, his own death at Daddy and Momma’s hands. The bridge was long and tall. Through a hole in the blanket, Jerry saw its steel girders high above stabbing through clouds, wrapped in sunlight. They tossed him over the rail, Momma and Daddy, and walked arm-in-arm away. Lying little bastard that he was, he wasn’t dead. His broken body tumbled through the air, stones, muddy water rushing, weeds awaiting it. He scrunched his eyes shut, cringed inside, hoped no one noticed; he thought.

It was a cold little house, full of shadow and dark windows. Daddy was drunk there and Momma was crying. Timmy always loved his father and hated him for making his mother’s life miserable. Timmy bit his lip and held his breath, then went where he was forbidden to go. The door, usually stuck tight, opened easily. He took this as a good sign, darkness would accept him. He slipped inside and eased the door closed, knowing his eyes would never adjust to the total pitch black but waiting anyway, standing on that top rickety step as soft things with sharp teeth scurried below.

Something with many feathery legs lit on his forearm, skittered across the fine blonde hairs on the face of his skin, its movement lighter than breath. His terrified voice screamed inside but no sound issued forth. He rubbed his arm in that spot, felt the tiny arc of weight the traveler of darkness made as it swung from the pendulum web it had launched on his skin.

“God’s creatures, Never smite them walking, only if on your skin or if they bite, then smite them and smite them well,” he muttered under his breath, repeating one of his Grandma Webber’s lessons.

The odor in that place was darker than ink. He breathed in deep and took the first step down. What damp embrace the womb of that room offered. It was warm in its earthen reek of soil, timeless and rotted root, kind to those who crawled and climbed, huddled in its midst. Timmy’s small hands grasped the wobbling plank at the side of the staircase. Its nails creaked in their steel-worm wooden homes as he leaned in and trusted it with his full weight.

Feet hanging loose and free, he searched with a naked toe through the broken top of his shoe for the first of the climbing holes they’d made, Timmy and his brother, Jerry. There... and there... solid earth; he let loose the plank, felt his legs take his weight, then dropped to the earthen face of the floor. With his back to the wall, he finally let the tears come, hot and salty, forging watery paths down the planes of his cheeks.

Timmy was ashamed of his tears, knew he would be before they began but was unable to hold them back. This wasn’t his first experience with shame, he’d had many; it felt the same, much like times before and since forever. Seven years old, with two younger brothers and a baby sister of two, he knew he had to be brave. Crying would only make things worse; there was never a reward for tears. He hugged his legs to his chest, then sobbed and sucked it in, a choking sound.

Timmy held his breath as his ears picked up some sound outside of himself. Squeak ... squeak, squeak. He exhaled, a gasp, an audible sigh. He could hear the voice of Jerry in his head, his best brother and only friend, a year younger than himself, taunting him. Timmy was older but Jerry knew things, things Timmy would like to argue away, but couldn’t… He felt a smile tug at his lips as Jerry’s voice spoke in his head. “They’re doin’ it, Timmy. Long as they’re doin’ it, they won’t be botherin’ us. We’re safe now.”

Timmy covered his ears with his hands, rocked back and forth in the dirt as the cadence of the squeaking increased. Dust drifted down from the floorboards above his head, a blessing of sorts from mother to son. He stood and brushed himself off, knowing she would seek him out after the squeaking. The climb holes were easy enough to find in the now not-so-dark. He climbed them up until he could grab hold of the old plank.

Timmy winced as a sliver of wood went in under the nail of his right index finger. He took a deep breath, found the top climb holes with his toes and swung his foot up to the step. Thin shafts of light made their way from the kitchen through the top and bottom edges of the door. He found the knob with his throbbing hand, twisted and gave the door a slight nudge with his shoulder. It refused to budge. Now it was stuck.

Timmy gritted his teeth and fought back the urge to cry out. Just as he was ready to give it another try, the door opened slowly and he almost fell into the kitchen. His mother stood there, a stern look on her face. She took a step back, hands on her hips.

“Timmy, you come out of there. How many times have I told you...” She paused, then lifted her thin arms, summoned him to her. “You’ve been crying.”

Relief flooded over him as he fell into her embrace. The top of his head just reached her chin and he nestled in, wishing for time to stop, no words. Just hold me on the mercy of your sweet breast. Those were Grandma Webber’s words about Jesus but Timmy only thought of Momma when they came to mind.

She pushed him gently away. “What were you doing down there? If your dad ever catches you...”

He held up his throbbing finger. “It hurts.”

She took it between her hands and raised it toward her face. Timmy giggled as her eyes crossed. “What?” she demanded with mock sternness.

“Your eyes,” he replied. “They got all crossed up.”

She held his finger tightly with one hand, and plucked deftly at the splinter with the other. Before he knew it, she’d kissed his injured fingertip and was pumping water, washing it off in the kitchen basin. “Now, what were those tears about?”

He held up his wounded hand. “It hurt real bad,” he explained.

“Don’t lie to me, Timmy,” she scolded. “You know you’re no good at it.”

He turned red and looked down at his toes, wiggling through the top of his shoe. “Why’d he have to whip Jerry so hard?”

Momma stood up straight, arms akimbo. “Your brother got just what he deserved. He was caught sneaking into the bread. H ate the last two slices. What am I going to put in your Daddy’s lunch tomorrow? It’s cold on the roof and he needs food to keep himself going. We’re broke and he doesn’t get paid until the roof’s finished.”

“That’s why I was crying,” Timmy said stubbornly, remembering the crack of the belt on Jerry’s bare skin while he bent over and held his ankles, trying not to fall over or cry, Daddy’s boots when he did.

Momma shook her head, frustrated. “I’m your mother; I don’t intend to stand around arguing with you about your brother. I’m going to lay down and have a nap. I have to go to work in a couple of hours. You keep an eye on your brothers and little Lisa. Wake me up at six.” She went back into the bedroom with Daddy.

Timmy left the tiny kitchen and went to the cramped living room, which served as day room and bedroom for Jerry, Peter, Lisa, and himself. The three boys slept on a convertible couch. Lisa had a makeshift bed in an old dresser drawer. Lisa was asleep and Peter was sprawled on the sofa. Jerry stood slumped in the corner where he’d been placed for further punishment. Timmy decided to take a short nap himself. He laid down on the floor so as not to disturb Peter. He bit down on his finger to alleviate the throbbing, then put his arm under his head and sang himself to sleep. “I was born one mornin’ when the sun didn’t shine.” Sixteen Tons was his favorite song. It was playing on the country western radio.

At five-thirty Timmy awoke and put a fire on low under the old tin metal coffee pot. He went back and sat on the end of the sofa, laid his hand on top of Jerry’s head. Jerry’s carrot-red hair stuck out between his splayed fingers.

“Sorry he spanked you,” Timmy whispered. Jerry groaned and pressed his small thin face into the hard scratchy corner of the wall. His hands bunched up into fists and he pressed them into the corner, causing his shoulder blades to stick out. Timmy thought he looked like a broken bird, a plucked chicken, too skinny for anyone to consider eating.

A few minutes before six o’clock Timmy went to his parents’ bedroom and entered quietly. He would watch them sometimes, faces moving, eyes twitching. Asleep, they were faces he didn’t know. He thought maybe he liked them better that way. He reached and touched his mother lightly on the shoulder. “No,” she mumbled, “No.”

Daddy’s eyes popped open. “Timmy, what the hell are you doing?”

The radio was playing Country Western. The family had two radios, one on the kitchen table and one next to the parents’ bed. There were three if you counted the one in Daddy’s old truck. The radios in the house were on twenty-four hours a day, always tuned to a Country Western station. The one in the truck was only on when the truck was running. Timmy wondered about that, whether the radio was off when the truck was off. The ones in the house were on whether his parents were home or not. Kids weren’t allowed to touch radios. “Wakin’ Momma,” he replied. “It’s just about six.”

Daddy rubbed a strong weather-beaten hand across his bleary eyes. “Shit! You go on, Timmy. I’ll get ‘er up.”

Timmy left the room as Daddy began to shake Momma’s arm. Timmy had always gotten on well with his mother but waking her or simply being around her when she woke up were experiences he wouldn’t wish on anyone. She was not nice then. She needed to be left alone. One hour up, maybe a bit more, then she became her almost agreeable self.

So, Timmy left them to it and went to play with his little sister, Lisa, who had just turned two. She was a cutie, the first girl after three boys. Daddy called her Punkin. Timmy tickled her and she giggled. He laughed with her until he felt Jerry glaring at him. Jerry treated Timmy poorly whenever he got punished. It seemed to Timmy that Jerry felt as if it was somehow his fault or like Jerry was receiving whippings on his behalf. He couldn’t figure it out. Jerry took the bread and ate it; Timmy didn’t.

All Jerry could do was look at Timmy mean and stare at him accusingly since Timmy was bigger and a lot stronger than he was. Momma told Timmy a story about when he was a year and a half old (he’s fourteen months older than Jerry), he would sneak in, take the top off Jerry’s bottle, and guzzle down his milk. He would screw the lid back on so no one would know he’d done it. Catching Timmy copping Jerry’s food explained part of the problem with his thinness but Momma resented him anyway. No matter what she did, Jerry had always been unhappy and undernourished.

Timmy heard the volume of the radio go up and the familiar clink of glass as Momma filled her and Daddy’s coffee cups. Smoke drifted through the wide arch between the living room and kitchen as they lit their Pall Malls. Daddy came into the room and plinked Jerry in the head with his finger. “Get your ass standing up straight. You don’t need to slouch around all day like a ninny.”

Timmy felt bad for Jerry as he cringed and shook with fear. The more fear he exhibited, the madder Daddy got.

“Turn around and come here,” Daddy ordered.

Peter was still sleeping, one leg hanging off the couch. As Jerry rounded the corner, his eyes riveted fearfully on Daddy’s hands, he bumped into Peter’s leg. Peter moaned, rolled over, fell off the couch, and began to cry. Daddy beckoned to Jerry with his finger. “Come here, asshole. Maybe I’ll knock you down on the floor; we’ll see how you like it.”

Jerry stood by the side of the sofa trembling. “No Daddy, please no.” Timmy saw a dark stain running down the front of Jerry’s trousers. He hoped Daddy wouldn’t notice. Sometimes, when Jerry was in trouble, he would mess himself which would only exacerbate his circumstances. Other times, when he wasn’t in trouble, he would mess himself which would start trouble anew.

“Tim,” Momma called from the kitchen, “Come on now. We have to get going or I’ll be late for work.”

Daddy pointed his finger at Timmy. “You put that little asshole in the corner and don’t let him out until I come home, understand?”

Timmy nodded his head. “Yes, Daddy.” Timmy glanced at Jerry, who stepped obediently toward the corner. Daddy gave Timmy a friendly wink and left the room.

Momma came in, picked Lisa up and kissed her chubby cheek. She glanced at the boys. “You guys behave yourselves and no going outside. Keep the door locked. Daddy will be right back to fix you something to eat. Lisa’s other diaper is soaking in the toilet. Rinse it out and hang it by the stove, Timmy. If she needs changed before it’s dry go ahead and use a dishtowel instead of a diaper. There’s one hanging from the oven handle on the stove.” She set Lisa on the couch, gave Timmy a reassuring smile, and hurried away.

The front door slammed shut. The children heard the sound of Daddy’s old truck starting up and pulling away from the curb. Jerry turned around, stared imploringly at Timmy. “Let me out of the corner.”

Tears brimmed up in Timmy’s eyes. He bit down on his sore finger to stop them. “I can’t, Jerry. He’ll find out, then we’ll all be in trouble.”

“How’s he gonna find out?” Jerry challenged. “Who’s gonna tell?”

Peter sat on the edge of the couch. “I will,” he said, a cruel grin on his little-boy face. “I’ll tell ‘cause you took the bread an’ got me in trouble. It’s all your fault. You knocked me off the couch when I was sleepin’.”

Jerry took a step from the corner, threatened Peter with a raised fist. “I’ll pound your face, you little brat! You ate half!”

Timmy ran between them, pulled Jerry’s arms behind his back and forced him back into the corner. He gave Jerry’s head a good bump against the wall for good measure. “Stay there! Don’t be picking on smaller kids!”

“Yeah!” Peter agreed smugly. “You’re a stealer, Jerry. You’re bad!”

Lisa began to wail. She was hungry, upset by all the commotion. Timmy picked her up and she stuffed a thumb in her mouth. She snuggled against his chest and closed her eyes, sucking contentedly.

Daddy didn’t come home after taking Momma to work. The Children were hungry, and there was nothing in the house to eat. Timmy pumped some water and they sipped at it but water is a poor substitute for food. Lisa and Peter cried and Jerry moaned and groaned, then finally slid down the wall and rested in a bony pile.

Timmy roamed around the confines of the shack, despairing for a crumb but, as on many a previous night, there were none. The night was long and the radio was singing. His siblings asleep, Timmy went into the kitchen and sat at the table. He rested his head on his arms, ignored the growling of his stomach and drifted into a troubled rest. A few hours later he heard a rattling at the door. He stepped quietly across the room and peeked out the window. It was Momma come home from work. As he unlocked and opened the door, a car pulled away. It was soon lost in its’ own steamy exhaust in the freezing winter night.

“Where’s Daddy?” Momma asked upon entering the house.

“He never came back,” Timmy replied, “I been worried.”

She kissed him on the forehead and handed him a heavy paper bag. It was greasy wet, close to falling apart.

“Never mind your Daddy for now,” she said, “Thank God for the Big Boy.”

Big Boy was the restaurant where Momma worked as a waitress. She wasn’t allowed to take food home but she would bus the tables she waited on and dump the leftovers from the plates in a bag she kept hidden in the kitchen. On nights when Alvin, the cook, brought her home she could sneak the bag out past the owner. The next trick was getting it past Daddy; he didn’t approve of his family eating garbage.

Momma touched Timmy’s face with her cold hands and kissed him again. She glanced at the clock radio wailing Country Western, Marty Robbins all dressed up for the dance. “Twelve thirty,” she murmured, “He’s probably at the bar. That gives us ‘til two to eat. You start sorting and fixing. I’ll get the kids.”

Timmy set the bag on the table and opened it. Though it was full of rotting salad, coffee grounds, and cigarette butts, all he noticed was the smell of food and best of all... meat! He grabbed a piece of chicken fried steak and wolfed it down, coffee grounds, cigarette ashes and all. He had never tasted better food. Momma came back into the kitchen and smiled at him while he wiped his face on his shirt- sleeve.

“They look so peaceful, I decided to let them sleep while we get everything ready,” she whispered. “Tonight we’ll have a feast. I see you found some of the steak. It was the Big Boy special today. There’s lots of it in there.”

They worked together to scrape cigarette ashes, egg yolk, coffee grounds, and soggy napkin off the meat, and began to warm it in a pan on the old stove. Experts at this, they even managed to salvage some mashed potatoes and corn on the cob from the bottom of the bag. The cigarette butts went in Momma's apron pocket to be worked on later. They didn’t have to wake the younger children as it turned out. Peter and Lisa came stumbling into the kitchen, their noses following the aroma of food cooking even before their eyes were ready to open. Momma smiled. “Go get Jerry,” she said to Timmy.

Jerry was standing up straight and stiff, nose stuffed into the corner. He flinched when Timmy touched his arm. “Come on, Jerry,” he whispered excitedly, “Momma brought some really good stuff home from work for us to eat.”

Jerry turned his head from the corner; eyes big and round, he stared at Timmy. His mouth made one word. “Daddy?”

Timmy tugged at his shirt-sleeve. “Come on, Daddy’s not home yet. You better hurry up!”

“Wait!” Jerry pleaded. “Is she... Is she in a good mood?”

“The best,” Timmy replied, “Now come on.”

Jerry shielded his eyes from the light as they entered the kitchen. They ate and ate, then sat around burping and smiling like contented chipmunks.

Suddenly Momma held her nose. “Jerry!” she accused, “You have peed and messed yourself!”

“It’s when he was scared, Momma,” Timmy interjected. “Before you ‘n Daddy left.”

Jerry’s eyes were wide, like an animal caught in the headlight beams of a car. Peter was smirking at him, enjoying his fear.

“Get out of my sight!” Momma ordered. “You’re disgusting. Scared is no excuse; we all get scared but don’t go around shitting ourselves.” She turned to Timmy. “You’d better stop making excuses for him. You’re not really helping and you only run the risk of getting yourself in trouble.”

As Jerry was leaving the room, there was a loud bang on the door.

“Oh my God!” Momma exclaimed, “He’s home. Timmy, get the bag; shove everything in it. I’ll try to keep him busy. You just...”

Glass shattered and the door caved in. Daddy’s voice interrupted, “Lock me outa my own Goddamned house!”

“Daddy!” Lisa called excitedly.

He staggered into the room, narrowing his eyes against the light. Shingle granules glistened on his jeans. He wore a small brimmed hat tilted over to the left side. Six feet tall, lithe of body, he was not a big man but certainly seemed so to his children as most fathers do, especially when he was angry or drunk, especially when he was both. He wanted to be a kind man but was nothing close to it when he had been drinking. On this occasion he had been drinking quite heavily all night long. “C’mere Punkin’,” he slurred. Lisa ran forward and hopped into his arms.

“Wassa matter?” He held Momma with an evil grin. “What I bring home ain’ good ‘nough? Your boyfrien’ Arnie been fuckin’ you in the garbage, then you bring it home to feed my kids, huh? Here, Timmy. Hol’ this baby girl for me.”

Timmy extended his arms and Lisa tumbled happily into them. Daddy took a step toward Momma, backhanded her to the floor. It wasn’t the first time Timmy hated his father. He was seven and a half years old. Maybe it was the first time he realized he would probably have to kill him someday. And, the most painful part of that realization, that he would love him when he did the deed. Stay down, a voice in his head begged Momma as she knelt where she had fallen. If you get up... She got to her feet and Daddy slapped her down again. Timmy carried Peter and Lisa from the room, around the corner from their fallen and bleeding mother.

“So!” Daddy’s voice trailed after them. “Where’s that little shit?” He staggered to Jerry’s corner, plinked him in the head with his finger. “Leas’ this l’il bastard stayed where I tol’ ‘im for once.”

Jerry was trembling awfully; Timmy could hear his teeth rattling, his skinny knees knocking together.

“Tim,” Momma laid a hand on Daddy’s shoulder. “Come to bed now, Honey. Come on... please.” Her tongue flicked at blood flowing from the corner of her mouth. Momma was beautiful and wore her fear well. She was very brave. Timmy was afraid for her.

Daddy plinked Jerry again. “Don’ relax, you l’il bastard; we gon’ pick this up tomorrow.”

He followed Momma through the kitchen, into the bedroom. The door slammed, followed by several slaps, screams, and thudding sounds. Timmy rocked his little sister in her dresser drawer until the bed springs in Momma and Daddy’s room began to squeak. Jerry was right; now they were safe.

Jerry turned, fixed Timmy with a stare from the dark hollow holes of his eyes. Peter and Lisa were sound asleep. Jerry’s eyes bored into him; Timmy was sad and ashamed, too confused to wonder why. He escaped Jerry’s accusing eyes for once, slipped away into a restless sleep, his hand rubbing Lisa’s back.

Morning came unexpectedly, dripping with new peril. “Where are your brothers?” Daddy was shaking him roughly awake. Timmy blinked up into his demanding face. Momma was standing behind him, one eye black and closed. Her lips were swollen, cracked, and dripping blood.

Timmy sputtered and looked around the room in confusion. Ten minutes later he was across the street in the park with Momma. The lilac tunnels of summer were closed, their bare branches locked, intertwined and reaching, hands empty. The sky was slate gray, a vast condemning face looking down, a mirror of the futility of their search. Timmy shivered. He felt his eyes tear up as he realized his brothers must be out here somewhere and that the world was an awful big somewhere. He closed his eyes, then opened them quickly because Jerry’s eyes were in there. They had told him the night before that they would be leaving; he felt it was his fault his brothers were gone. The awful realization that he should have known that which it was impossible to know gnawed at his senses.

Timmy and Momma followed the two small sets of footprints in the fresh snow, across the street and into the park, down to the round empty swimming pool. A friend of Timmy’s had taught him and Jerry to ride a bicycle in that swimming pool in the autumn when it was emptied out. Timmy felt tears coming when he remembered Jerry spiraling in toward the center and crashing every time he mounted the bicycle.

Timmy stooped down to pick up a cigarette butt from the snow. He already had a pocketful of them. Gathering cigarette butts from gutters and walks was natural for him, an old habit from his first memories. He and Momma would take the butts home where he would help her empty the papers and grind the tobacco together; then she would roll them into smoking sticks for herself and Daddy.

“Never mind that!” Momma said tersely. She was crying, the wind had begun to blow. Tears were frozen on her battered face. The footprints meandered around the swimming pool and out of the park on the other side. The walks had been shoveled there, leaving mother and son nowhere to follow. They went home and found Daddy sitting in the dark little kitchen next to the old stove. Lisa was playing happily in his lap. He had a cold beer in one hand, a Pall Mall in the other.

Momma choked back a sob. “We followed their footprints through the park,” she stated softly, treading carefully, “It’s awfully cold out there. A child could freeze to death.”

Daddy snorted and shook his head. “Don’t be so dramatic, Kathy. It’s only been a couple of hours since we got up. If we don’t hear somethin’, say by noon, we’ll call the police. We both know it’s just Jerry pullin’ his usual shit, draggin’ his little brother along to cover his ass.”

“But they may have been gone half the night,” Momma protested.

“Don’t think so,” Daddy replied in a calm and matter-of-fact tone, then to Timmy, “When did you go to sleep, Timmy?”

“After you,” Timmy replied, “I was rocking Lisa, then went to sleep on the floor. Jerry was in the corner and Peter was asleep on the couch.”

Momma paced back and forth a bit, then, “I’m going to the corner store. Maybe they’ve been there. Can I have a dime for the phone?”

Daddy set his beer down. “I’m not made of money, woman.”

“I... I gave you my tips last night,” she stammered. “There were dimes and nickels.”

Daddy set Lisa on the floor where she began to roll empty beer cans around. “Choo choo... choo choo. Lisa make train. Choo choo.”

Daddy leaned back in his chair, reached deep in his pocket. Timmy was afraid of the look on Daddy’s face. Nothing good ever happened when he looked like that. He threw a handful of change in Momma's general direction. “I make more money by accident than you do on purpose, you stupid bitch. Take your nickels and go call the cops. That’s all you want to do anyway.”

With one eye on Daddy, Timmy scrambled to help her pick up the change. He and

Momma hurried out the door and down to the corner phone booth. Momma began to cry.

She held Timmy close as she spoke to the police dispatcher.

When they got home, Daddy offered Momma a weather report. According to him, the wind had blown the clouds away so it was warmer. He was going to pick up his helper, a man he called Dee-Dot, and try to finish the roof he’d been working on. He gathered his tools and left them there. Timmy worried about his brothers while he kept an eye on Lisa. Momma fussed about, hugged herself a lot, touched Timmy and Lisa, straightened the house.

A little while later, two policemen came to visit. They asked Momma a gazillion questions. To Timmy’s surprise, one of them took him out to the police cruiser by himself while the other one stayed inside with Momma.

“Do your mother and father ever hit you and/or your brothers and sisters?” the man asked Timmy.

To which he lied, “No Sir.”

“What happened to your Momma's face?”

To which he lied, “I don’t know.”

“Are you afraid of us?”

To which he answered truthfully, and with relief, “Yes, awfully.”

“Are you afraid of your parents?”

To which he lied, “No Sir!”

And so on; Timmy was seven years old. He knew better than to cooperate with the police.

They seemed to stay for an awfully long time and, before leaving, promised Momma they would broadcast a story about the two missing boys on the television news. The only picture she had to give them was of Peter after he drowned in the irrigation ditch the year before. He fell in the ditch that ran behind the motel the family was living in. A crazy man who lived by himself in a run-down house the other side of the ditch saw Peter’s cowboy boots go floating by. Crazy as he was, he figured there might be a little boy inside them so he jumped into the ditch, pulled Peter out and saved his life. Peter looked cute in the newspaper photograph, sitting in a hospital crib. The police sent a lady out later who penciled out a fairly good likeness of Jerry from Momma's description.

The Turner family didn’t have a TV, so they didn’t see Jerry and Peter on the Billings News. Daddy saw it though, on a television at the bar. He was upset over the broadcast, since the newsman said police had yet to interview the father; a statement which, to him, implied that he was under suspicion. If Peter wasn’t missing, Timmy would have been suspicious too. Daddy seemed to favor his youngest son as much as he despised Jerry. He would never do anything to hurt Peter.

To say simply that Timmy feared for Jerry is somehow making light of that emotion, the frail breath of their lives in general. Fear was a tangible aspect of their day-to-day existence: fear the police would throw Daddy in jail when he was drunk, fear they’d let him out when they did, fear he’d hurt Momma. Most times fear would even dispel the rampant rumble of the children’s ever-present hunger, fear that Daddy had killed Jerry.

The next day Daddy had to go the police station for an interview. A nice lady came by with commodities for the Turner family. Momma fixed Cream of Wheat for breakfast, Spam for lunch. For once Timmy had no appetite. Momma stayed home from work, Timmy didn’t go to school. She was so fidgety and nervous; she kept crunching up the cigarette butts. Her hands were shaking so bad, she wrecked the cigarettes in the roller. She’d put the mess down and hug Timmy, again and again. “You’re my big strong boy, Timmy, my big strong boy. You’ll never run away from your Momma.”

Daddy came home in a terrible mood. It was fairly warm, so he sent Timmy outside to play with Lisa. The tiny house was situated on the edge of a packed-dirt courtyard along with a half dozen other one bedroom rentals. There were lots of toddlers and Lisa, being an agreeable and sweet child, joined right in and began to play with them.

Timmy sat in the yard watching Lisa play. He got to thinking about a girl he liked in school. She wore glasses and was real smart. His eyesight was terrible so he was unable to make out assignments written on the blackboard. She would whisper whatever was written there to him. This was a real life saver to Timmy because teachers became exasperated with him, after moving him to a desk in front of the class, when he told them he still couldn’t read what was written on the blackboard. Some teachers accused him of angling for attention because no one could be that blind. The last thing Timmy wanted was attention.

Sometimes after school Timmy and the girl would meet on the corner of the block. She’d take off a gold necklace she wore. They would swing it round and round between them while they talked. On Fridays, students who aced their spelling test were rewarded by being allowed to slide down the fire escape at school. This was fun and exciting because the school was four stories high. The fire escape was a spiral tube constructed of fifty-five gallon oil drums and situated, top to bottom, into the inner workings of the brick structure. Timmy was a very good speller and so was his friend. Fridays were extra special to them. She was his very first crush. Her name was Jackie.

That night, the second night Jerry and Peter were gone, Lisa and Timmy were sent to bed at eight o’ clock. Momma hung a blanket across the archway between the dayroom and kitchen. Timmy snuggled up with Lisa on the couch and listened to the hushed tones of his parents talking. He couldn’t distinguish the words over the music from the Country Western clock radio. There was a frantic urgency in the gist of their conversation and, terrible for a child, that feeling when parents are afraid of circumstances set in motion over which they have no control.

The next morning the family was awakened by police at the door. An officer handed Daddy an official looking paper. He stepped through the door as he asked if it was okay to do so. He told Daddy to turn the radio off so they could talk without it in the background. Daddy did as the man asked but Country Western music could be faintly heard from the parents’ bedroom. Timmy could tell Daddy was mad. He didn’t like anyone telling him to turn off his radio but he didn’t say anything to the policeman. The police were mean serious and all business.

There were six of them this time. They looked big and threatening in the tiny house. One of them even had to bend over to keep from bumping his head when he passed through the arch into the room where the children slept. Lisa and Timmy sat in a corner while two policemen lifted the couch and shined their lights underneath it. The big one shook his head. “Cockroaches.”

His partner lifted Timmy and Lisa’s cover from the couch, then dropped it disdainfully. “Infested with bedbugs,” he said as he cast them a sympathetic glance. His sympathy was lost on Timmy; he was embarrassed and afraid, too worried about his brothers to care much about bugs and policemen.

“Hey, Sarge.” a voice called from the kitchen, “Come check this out.” Timmy was surprised when the smaller policeman answered the call. He was sure the big one would be the boss. Lisa wiggled in his lap and tried to follow the man. Timmy held her tight, tickled her to make her laugh and keep her busy.

“Timmy, come here,” Momma called out.

He stood and hoisted Lisa up onto his hip. She was a chunky girl. It took a lot of courage to lift the edge of the blanket and pass from the security of the living room into the tiny kitchen packed with grownups, but Timmy managed the task.

The policemen had opened the door to the dirt room, and were huddled around the doorway. A couple of them were pointing their long powerful flashlights down into the gloomy space. “So you say you’ve never been down there,” Sarge said to Daddy.

Daddy sat at the kitchen table, one leg crossed over the other, drinking coffee and chain smoking Pall Malls.

“Nothing down there but dirt,” he replied, “I was gonna store shingles and tools down there, but the steps are broken; it’s not worth the trouble to fix them.”

“How ‘bout the kids?” the policeman pressed, “Do they go down there to play?”

“No way!” Daddy said indignantly, “There’s bugs and stuff down there. It’s not safe. I wouldn’t let my kids go where I wouldn’t go myself.”

“Someone’s been down there, Sarge,” one of the policemen interrupted.

“Timmy,” Momma said, with a flat edge to her voice.

“It was me,” Timmy croaked, “I climbed down there yesterday.” He could feel his ears hot and burning red.

“Damn it, Timmy!” Daddy scolded, “I told you...”

“That’s enough!” Sarge leveled a warning glare toward Daddy, then turned to the other policemen. “Bentley, get those shovels out of the trunk of the car.” His gaze returned to Daddy. “You’re a roofer?”

“I’m a roofer,” Daddy replied, defeat evident in his voice.

“You wouldn’t happen to have a ladder that would fit through this door, would you?” Sarge asked.

“Timmy,” Daddy said, by way of reply, “Go get the chicken ladder off my truck.”

A chicken ladder is a handmade wooden ladder that roofers use to climb up the face of steep roofs from a plank scaffold. Timmy left the room, relieved to go outside, elated to have something to do. The cold Montana air felt great in his lungs as he squinted his eyes to shield them from the sun. There were police cars blocking the courtyard. A few men from the neighborhood were huddled off to one side smoking cigarettes and staring at the house. Timmy felt naked and uncomfortable under their gaze. He ignored them as best he could while he twisted the shingle wrapper wires holding the chicken ladder to the rack of the truck. Once he got it loose, he pushed it toward the rear of Daddy’s truck.

“I got it, kid.” Timmy was startled, jumped and banged his head on the ladder rack at the unexpected sound of a voice. The big cop grinned and patted him on the head.

“Sorry kid, thought you knew I was behind you.” He picked up the heavy two by four ladder like it was light as a toothpick and carried it into the house.

Once inside, he poked the ladder through the doorway off the kitchen and down into the dirt. Someone had rigged a hundred watt trouble-light to better see. Spiders skittered across the broken shelves of the old root cellar.

“Got anything to say before we go down there?” Sarge asked Daddy.

Daddy stood up and put on his hat. “Yeah, I got a roof to put on.”

“Sit down!” Sarge growled. “You’re not going anywhere until I say so.”

Daddy sat down but kept his hat on. Two policemen set their heavy belts with guns, night sticks, and flashlights in the corner by the stove. They tossed their hats on top of the pile, threw shovels into the hole, and followed them down. They worked in twos, digging sideways and down, until late afternoon.

The kitchen floor was crusted with dirt and mud, the air close with the heat and palpable tension of too many bodies in too small a space. Sarge ordered the men from the hole and sat down wearily across the table from Daddy. “Where are they?” he whispered in exasperation.

Before that day, Timmy had never seen Daddy cry. He took a handkerchief from the back pocket of his trousers, blew his nose loudly. He looked imploringly at the policeman. “God as my witness, sometimes I’m not much of a husband or father but, I would never hurt my children. Please go and find my little boys.”

Sarge stood up. “Oh, we’ll find them; you can bank on that. Let’s just hope we find them in one piece.”

Momma was scooping up dirt with a piece of cardboard, dumping it in a box.

“Ma’am,” Sarge addressed her, “Sorry about the mess. We’d be glad to help clean up.”

“You go to hell!” Momma cried. “My boys are somewhere out there. You come in here and ... and ...”

She dropped the cardboard, stood up straight, then wrapped her arms around herself and shuddered a weeping despair. Timmy stepped in front of her and glared at the policeman. The man shook his head sadly and followed his men into the yard.

Neighbors came knocking after the police left, but Momma refused to answer the door. Timmy helped her make grilled cheese sandwiches with the commodity cheese. Daddy turned up the Country Western. Lisa and Timmy went to bed early. He got to thinking about the bed bugs and tried to locate them in the darkness by feeling around with his fingers. He could never find them, but could feel them crawling. He woke up every morning with red itchy bumps; at least now he knew why.

The next morning, Momma told Timmy to go to school. Some days he was glad he couldn’t make out things with his eyes until they were a couple of feet away. This was one of those days. He felt the eyes of his classmates on him, heard some of them snickering, but was fairly safe in his fuzzy cave.

“Did they find your brothers?” Timmy flinched as the teacher placed her hand on his shoulder. He shook his head, stared at her hand. She gave him a reassuring pat, then returned to her desk.

Timmy’s girl, Jackie, wasn’t at school that day and he was glad of that because he felt all messed up, confused inside. He was relieved she wasn’t there but, for some reason, it made him want to cry. He couldn’t remember what the teacher was writing on the board but she left him alone that day, a mercy. When the bell rang, he ran outside and stood on the corner. It would have been nice to swing that gold chain and look into the eyes Jackie was kind enough, eager even, to share.

The first thing Timmy noticed when he entered the house was Jerry and Peter sitting on the couch. There were empty boxes stacked in a corner of the kitchen. Momma was bent over, pulling pots and pans from a cupboard. “Timmy!” she said excitedly, “We’re moving back to Colorado.” She cast Jerry a sidelong glance. “There’s no way we can stay here now.”

“Wha ... Wha ...,” Timmy mumbled.

A car honked outside. Momma's hands went to her hair and fluttered about like lost birds. She grabbed her coat and purse, kissed Timmy on the forehead. “Watch them,” she said meaningfully, nodding her head toward Jerry and Peter. “Daddy’s finishing a roof, so he’ll be home late. I have to go to work.” She kissed Timmy again as the car continued to honk, then rushed out the door.

Timmy dropped his books on the floor and went into the living room. “What?” he asked his brothers. “Where’d you go?”

“We got a ride in a police car,” Peter chirped.

“But how?” Timmy continued, eyes wide, mouth open in an expression of disbelief.

“They caught us stealin’,” Jerry said, “an’ brought us home. Oh boy.”

“Does Daddy know?” Timmy asked incredulously. He wondered to himself why Jerry wasn’t being severely punished.

“He was here when they brought us home,” Jerry replied.

Timmy wanted to hug him but knew Jerry would have none of that.

“Aren’t you in trouble?”

“He’ll get me later,” Jerry said matter-of-factly. “I think those policemen scared him.”

Jerry and Timmy sat in silence as Peter snuggled next to Lisa on the couch. Soon the younger children were sound asleep. Jerry put a finger to his lips, stood up and motioned for Timmy to follow him. He opened the door off the kitchen and made his way clumsily down the broken cellar steps.

As Timmy hung from the creaking rail, his eyes were assaulted by a bright beam of light. He fell onto a pile of freshly-dug Earth. Jerry sat there clutching a shiny new flashlight, a self-satisfied smirk on his face. He reached into a bag, tossed Timmy a Hershey bar, then took one for himself. “It’s all out there,” he murmured., “Alls you gotta do is take it.”

Timmy gobbled the Hershey and Jerry gave him another. “You shouldn’t have run away,” Timmy said.

“Someday they won’t catch me,” Jerry murmured, “An’ I’ll never come back.”

Timmy licked the chocolate from his fingers. “Why’d you take Peter?”

Jerry shook his head. “The little brat woke up when I came out o’ the corner. Said he’d squeal if I didn’t take him along. I woulda been better off by myself.”

Timmy crumbled a clod of dirt in his fist. “The police thought you guys were buried in here.”

Jerry put the flashlight to his chin, making a grotesque mask of his thin face. “I wish I was, I really do.”

Daddy came home from work and finished the packing. He cleaned the house and made a bowl of popcorn for everyone to share. Timmy noticed his hand shaking as he sipped his coffee and stared at Jerry. Daddy was a good and thoughtful man when he was sober.

Next day Timmy helped Daddy load the truck and the family headed south back to Colorado, the state where all the children had been born. Lisa and Peter rode up front in the cab of the truck with Momma and Daddy. Jerry and Timmy sat in the back, nestled between boxes of the family’s meager belongings. There was a tarp fastened over the top and sides of the ladder rack to keep out the weather. Jerry smiled thinly at Timmy, winked and handed him a Hershey bar.

“How’d you get that stuff in here?” Timmy asked, gesturing toward a paper bag in Jerry’s lap. “Daddy would kill you if he caught you sneakin’ stuff like this. How’d you get it down in the hole at home in the first place and keep it secret from Peter?”

A knowing grin came over Jerry’s freckly face. “A guy’s gotta cover ‘is stash; don’t tell Peter. He’s too stupid t’ figure it out for himself.” Jerry looked a hundred years old to Timmy at that moment. Shortly thereafter he dozed off, and Timmy did what he’d been waiting to do since he came home from school and saw Jerry sitting on the couch. He touched his skin with the tips of his fingers and kissed his sleeping child’s face. Jerry groaned deeply and touched where Timmy’s lips had kissed. In a small voice he whispered, “Daddy.”